Find your winery or vineyard

1 Wineries and Vineyards for sale in Sicily

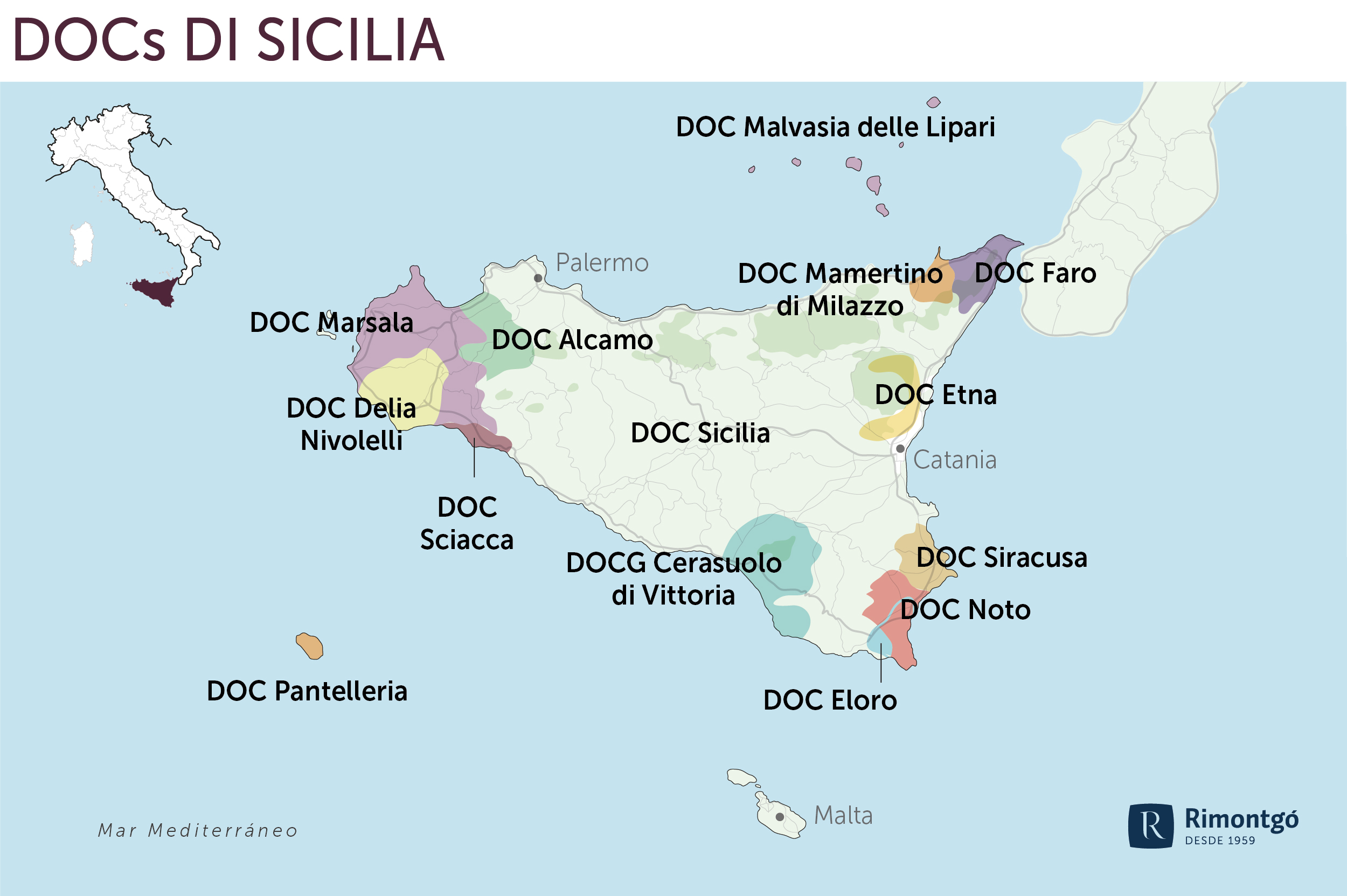

Infographic of the Denomination of Origin

Change to imperial units (ft2, ac, °F)Change to international units (m2, h, °C)

Sicily

HISTORY

Ancient writings and current research seem to confirm that vine cultivation and winemaking techniques were introduced to Sicily by the first Greek settlers. Various testimonies, such as Aristotle, Ipius of Reggio (historian of the 5th century BC), Archestratus of Gela (poet and gastronome of the 4th century BC) and, above all, Diodorus Siculus, show that, in ancient times, a wine called Pollios was produced in the area of Syracuse, in honour of Pollis of Agro, the mythical tyrant, who had spread it throughout Sicily (VIII-VII BC). This wine was derived from the Byblia variety, which originated in the eastern Mediterranean (the Biblini mountains, Thrace). Moscato di Syracuse seems to be the original of this wine, as the historian and oenologist Saverio Landolina Nava (1743-1814) claims, referring to a fragment of Zenobius from the 1st century A.D., on the basis of which we could classify this wine as the oldest in Italy.

The origins of Malvasia de Lipari wine also seem to date back to the Greek colonisation of Sicily and thus of the Eolean islands, according to Diodorus. This complex and concentrated wine was and is known as one of the most aromatic and ancient wines of Sicily. In The Wandering Life, the French novelist Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893) describes Lipari Malvasia as follows: ‘It resembles sulphur syrup, dense, sugary, golden and with a sulphurous taste, characteristics which make it seem like the devil's wine’.

According to Stardone and Athenaeus, from the late Republican period of the Roman Empire, the sweet and light Mamertino wine, produced in north-eastern Sicily, was appreciated by many, including Julius Caesar, and exported to Rome and Africa. In the Middle Ages, around 1600, Malvasia di Lipari, for its sweet taste and aroma, was compared to the wines produced with the Muscat variety. In 1596, Andrea Bacci described it as a ‘sincere’ wine, comparing it to the more famous Mamertino.

Pliny the Elder, however, favoured a sweet wine produced near what is now Castel di Tusa (formerly Halaesa), where in the 2nd century BC bronze coins were minted with symbols alluding to viticulture. Little is known of Inykinos wine, sweet and very good according to Fozio, from the city of Inykos (perhaps in the Belice valley).

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the cultivation of vines and the production of wine were drastically reduced also because of the various and continuous dominations that the island of Sicily has undergone. The introduction of Muscat of Alexandria on the island of Pantelleria is due to the Arab domination, and even today the grape variety retains the name zibibbo from the Arabic ‘Zibib’ (cape Zebib in Tunisia). The Arabs remained in Sicily from 853 to 1123 A.D. and introduced the technique of vine cultivation, but also the raisining of grapes, a technique that has been maintained to this day. In 1696, Cupani refers to the presence of the zibibbo variety in Sicilian vineyards.

However, from the 1400s onwards, but especially at the end of the 1700s, a large oenological industry arose in Sicily, producing the famous Marsala wine, which is still famous today. It was in 1773, when John Woodhouse, an English merchant, arrived in the port of Marsala seeking refuge from a sirocco storm. He tasted the strong, robust local wine and shipped it to England, but added wine spirit to each container to prevent it from oxidising during the sea voyage. Marsala was a great success; the Woodhouse family began to invest in Sicily, so that by the end of the 18th century it was being drunk on all the ships of Her Britannic Majesty. After the Woodhouses, other Englishmen came to Marsala, the most notable of whom was Benjamin Ingham, a businessman based there since 1812; he too founded a winery, becoming in 1851 the richest man in Sicily. In 1832, Vincenzo Florio and his son Ignazio moved to the island to compete with these two British winemakers, thus becoming an active part of the Sicilian bourgeoisie. Finally, in 1860, when Garibaldi and his Thousand landed and conquered Sicily, they celebrated by drinking and toasting with Marsala wine; the historic toast of Dumas and Garibaldi is still remembered.

Until the contemporary age, Sicily's historic wines were sweet, but red wines are now the island's most recognised wines. Ironically, the near-perfect conditions for vine cultivation played a key role in the downfall of Sicilian wine in the late 20th century. Sicilian winegrowers pushed their vineyards for high yields that led to unbalanced, flavourless wines and a drop in quality and consumer confidence. Fortunately, the movement to reverse this reputation is underway, and Sicily is now one of Italy's most promising and interesting wine regions.

It is from the 1960s and 1970s onwards that Sicilian viticulture began to change, thanks to the likes of Giacomo Tachis, and bottled wines began to be marketed outside of bulk or demijohns in Western Sicily. Enrico was the first great wine that became known in 1984 because it was the first real commitment to high quality. It was followed by Rosso del Conte with a bit of perricone. The definitive change came in Sicily in 2000, when the varietal distribution was 25% in reds and 75% in whites. In that period, the extension of the Nero d'Avola increased by 33%. There is a succession of plantations, the big wineries are betting on it.

TYPE OF GRAPE

The most representative red variety of the island is, without a doubt, the Nero d'Avola, with more than 18,000 hectares of vines planted, being the second most cultivated variety on the island after the white Catarratto. Nero d'Avola is tannic, with good acidity and a medium structure, giving fruity wines with clear notes of cherry, especially when young.

There is not much precise information about its origins. For a while it was thought to be a relative of the Syrah, which on its journey from Asia to France would have stopped in Sicily, but that will be determined by DNA. We do know that before it was known as Nero d'Avola it was called Calabrese, the name by which it was known throughout the 19th century. Bacci speaks at the end of the 16th century of ‘wine made for calibrese use’ in the province of Catania. At that time it was associated for the first time with the small village of Avola in the province of Syracuse. Calibrese, however, does not come from Calabria but from an Italianisation of the Sicilian dialectal term ‘calavrisi’ which is ‘grape (cala) of Avola (vrisi)’. The ‘uva’ was later replaced by ‘nero’. Capuani, in 1616, speaks of ‘calavrisi with round berries’. However, it was not until the 18th century that the variety began to be mentioned with some frequency. It was present in Avola until the end of the 19th century, when phylloxera arrived. From here it travelled to the Noto Valley and from there it began to spread all over the island. In 1870, Angelo Nicolosi already warned that it was one of the highest quality grape varieties in existence. Therefore, it does not come from either the centre or the west of the island, where it is more widespread today. It was found in the areas of Avola, Noto, Vittoria and Pachino and from there it spread throughout the island. The character of the original area has nothing to do with that of the adopted areas. It is present all over the island except in the Etna area.

It is a difficult grape variety to mature, which is one of the reasons why it is blended with French varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah (especially the latter), some with Sangiovese to add a little acidity, in order to refine the wine and make it softer without losing its enormous personality. It harmonises much better with perricone or frappato. Or on its own, as most producers have been doing for the last decade and a half. The macerations were very short until the arrival of Tachis, invited by Diego Planeta, who recommended longer macerations in order to achieve a better texture and more structure.

Other red grapes that can be considered typical of the island are pignatello or perricone, with a fruity character and very easy to drink, and frappato, finer and with less colour. The sister varieties Nerello Mascalese and Nerello Cappuccio are also small players in terms of volume, but are of vital importance throughout Mount Etna. Other local varieties are Grecanico, Alicante (Grenache) and Nocera. A bet that in Sicily is having a lot of success in recent years is the wines made with international varieties, especially as single varietals, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah in particular.

Whites account for around 70% of the island's production and occupy a more than respectable area of vineyards. The most representative white variety is the catarratto, a grape that produces wines with a very balanced aroma, flavoursome and well-structured. With a more marked nose are the wines based on inzolia, the Tuscan ansolica, while the grillo variety is more concentrated, with more flavour and salinity, also ideal for the production of Marsala wines. Among the aromatic varieties, the wines based on moscato d'Alexandria, known here as zibibbo, ideal for dry vinification and unforgettable as passito di Pantelleria, obviously stand out. As for the international varieties, chardonnay is one of the best-performing grapes in Sicily, generally suitable for a certain amount of ageing.

D.O./Valle (wine regions)

Discover more wineries and vineyards for sale in these wine regions in Islands

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive news about wineries and vineyards.